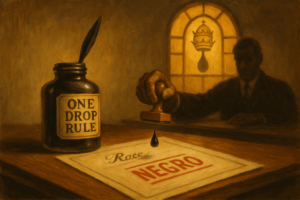

Berlin, 1933

The crowd gathered in the torchlight. Drums beat against the night as banners unfurled across the square. The Reichstag fire had just gutted Germany’s parliament building, and emergency decrees followed like a shadow. Newspapers were silenced, opposition leaders arrested, protests broken up. Within weeks, the Enabling Act would pass—handing Adolf Hitler the power to rule without parliament, dissolving the fragile Weimar Republic in a stroke.

On those streets, people could watch a democracy slip away almost in plain sight. To some, it looked like spectacle—flags and marches. To others, it seemed temporary, a fever that would burn out. And to many more, it looked like politics as usual, messy but survivable. Only later would it be clear that the line had already been crossed. Fascism had seized the state, and the cost of undoing it would climb beyond imagination.

That scene in Berlin is not distant history. It is a warning.

The Myth of Three Outcomes

It has been said there are only three ways fascist regimes end: stop them before they seize power, defeat them in war, or wait for them to die with their leaders. The formula is sharp, but it is incomplete. History is broader, more surprising, and sometimes more hopeful. To insist on only three outcomes is to risk two illusions: fatalism (“once they win, nothing can be done”) and complacency (“time or war will solve it for us”). Both are dangerous.

Prevention: The First and Best Line of Defense

The surest way to stop fascism is before it takes power. Once inside the state, it rewires institutions to protect itself. Prevention may look messy—lawsuits, awkward coalitions, contested elections—but it is far less costly than the alternatives.

France has lived with this reality for decades, where the far-right has repeatedly advanced deep into presidential elections but never captured the state. Brazil faced its own test in 2022 when Jair Bolsonaro undermined courts and elections. He lost, and under immense pressure, he left. These examples are reminders that early vigilance can hold the line.

When Prevention Fails: War

If fascism consolidates, the exit has often been catastrophic. Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy were not dismantled by votes but by invasion. Hitler’s Reich collapsed only after six years of global war and tens of millions of dead. Mussolini’s dictatorship ended in 1943 when Allied troops landed in Sicily and his own Fascist Grand Council turned against him. Japan’s militarist regime, while different in structure, also ended only after total defeat and atomic fire.

These stories reveal the cruel price of waiting too long: war as the only solvent strong enough to dissolve regimes that appear immovable.

The Long Wait

Not every dictatorship falls to war. Some simply outlast generations until leaders die or lose their grip. Franco’s Spain limped on for nearly forty years, silencing dissent until the dictator’s death in 1975 finally opened the door to democracy. Portugal’s Estado Novo, begun under Salazar, staggered into the 1970s until young officers, weary of colonial wars, staged the Carnation Revolution, a coup that met cheering crowds rather than resistance. Pinochet’s Chile lasted nearly two decades before a plebiscite in 1988 forced a transition to democracy.

Waiting is an option. But it is an option that condemns societies to decades of fear, silence, and exile.

The Cracks in the Wall

To reduce the history of fascism to war or death is to overlook the cracks that have opened from within. Mussolini’s fall was not simply imposed from outside—it was his own inner circle that betrayed him when war made him expendable. Portugal’s Estado Novo collapsed in a day when soldiers and civilians turned on the system simultaneously. Chile’s dictatorship fell not with gunfire, but with ballots, when millions voted “No” to Pinochet’s continued rule.

The late 20th century added more examples. Eastern Europe in 1989 saw Communist regimes collapse one after another: Poland’s Solidarity forced elections; East Germans filled the streets until the Berlin Wall cracked; Czechoslovakia’s Velvet Revolution toppled its rulers in weeks; even Romania’s Ceaușescu fell, though only after a violent revolt. In South Africa, apartheid ended not through war or the death of its architects, but through international pressure, economic crisis, and the determination of its people. Mandela’s release in 1990 and the first multiracial elections in 1994 were proof that negotiated transitions could dismantle even deeply entrenched systems.

These cases show that fascism and authoritarianism are not invincible once rooted. They are brittle under pressure, vulnerable to fracture, and sometimes forced into retreat.

The Balanced Reality

Across these histories, one pattern holds: the longer fascism endures, the more brutal the cost of removing it. War destroys regimes but at a scale of devastation measured in generations. Waiting for leaders to die means decades wasted in repression. Even uprisings and negotiated exits leave scars—Chile’s referendum was followed by years of reckoning, and South Africa’s transition carried both triumph and pain.

Which brings us back to Berlin in 1933. People there believed institutions could contain a demagogue. Others assumed the fever would pass. A few saw the danger clearly, but their warnings were drowned out by fatigue and misplaced faith in “normal politics.” By the time the truth was undeniable, the cost of undoing fascism had grown almost beyond imagination.

We are not in Berlin in 1933. But we are at our own crossroads. The uniforms are gone. The marches unfold on digital platforms as much as city streets. Yet the pattern is familiar: leaders who undermine elections, courts bent to political will, violence first excused and then encouraged, the steady erosion of trust in democracy itself.

The question is not whether fascism can be defeated—it can. The question is whether we act before the cost rises too high. Because history’s final verdict is always the same: fascism does not vanish on its own. It must be confronted. The longer it takes root, the higher the price of uprooting it. Prevention is not simply strategy—it is survival.

Add your first comment to this post